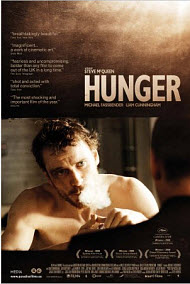

Hunger

Ireland: 15A / UK: 15 / Australia: MA / France: -12 / Portugal: M/16 (Qualidade) / New Zealand: R16

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | History Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 36 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2008 |

| USA Release: |

September 27, 2008 (New York Film Festival) December 5, 2008 (limited) March 20, 2009 (expansion) DVD: February 16, 2010 |

Irish issues: Commentary One and Two

About murder in the Bible

Other movies about Irish politics and resistance: Others about Ireland and Irish:| Featuring | Michael Fassbender, Liam Cunningham, Stuart Graham, Liam McMahon, Brian Milligan, Helena Bereen, Larry Cowan, Rory Mullen, Lalor Roddy, Laine Megaw, Dennis McCambridge |

| Director |

Steve McQueen |

| Producer | Blast! Films, Broadcasting Commission of Ireland, Film4, Northern Ireland Screen, Wales Creative IP Fund, Iain Canning, Peter Carlton, Edmund Coulthard, Robin Gutch, Laura Hastings-Smith, Linda James, Andrew Litvin, Jan Younghusband |

| Distributor | IFC Films |

“An odyssey, in which the smallest gestures become epic and when the body is the last resource for protest.”

Good Irish drama can transform the everyday morose and squalid into something universally poetic and sublime. Outside every dank cottage that Sean O’Casey, John M. Synge, Brian Friel or Conor McPherson sets their action in lies a long dark road. Inside that cottage you know you’ve reached the end of that road. A life may be lost or misplaced along that path, but inside the cottage, a soul is found.

Irish poetry that stirs the heart on stage or keeps you in its grips for hours in a pub has always been missing from Irish films. The sweetness of tragedy doesn’t come through on the screen; you see the thorns, but the rose petal are invisible. Irish art is more heard than seen, which is a good thing, since the Irish are at their best when they’re talking.

A new film, “Hunger,” by first time director, Steve McQueen (no, not that Steve McQueen) and screenwriter Enda Walsh, is an exception to everything I just did quite a bit of talking about. “Hunger” is a quiet film; long segments visually play out with no dialogue at all, a lot of the action takes place off-screen, and the film’s slow-paced but moving final scenes are a marvel of how much can be said with so little.

There is virtually no sound in those final scenes. The predominant color is white, which outlines the changing color of flesh as it goes from a healthy state through phases of decay to ultimately death. Quite literally, and as if in real time, we see human flesh corrupt before our eyes.

The action of “Hunger” takes place in Belfast’s Maze Prison in 1981. Maze, built in 1976, housed prisoners, mostly members of the Irish Republican Army, who had committed or colluded in terrorist acts. In Maze, they were stripped of the political prisoner status they were given in other prisons, and were treated as common criminals.

The prisoners rebelled against their new status by rejecting prison uniforms (they wrapped their naked bodies in blankets), refusing to bathe or shave, smearing their cell walls with their own excrement, and using their food rations to form a well around their prison doors through which they could pour their own urine and thus flood the prison hallways.

The prisoners’ protests had little effect on the prison guards or on the British government. The authorities continued to refuse the prisoners’ requests for upgraded status; the guards only accelerated their mistreatment of the prisoners, and even taunted them by offering them civilian clothes made of stripes and plaids that were hideous even by 1960s Carnaby Street standards.

One prisoner, the iconic Bobby Sands, decides to lead a prison hunger strike. He resolves not to accept food or water until his and his fellow prisoners, demands are met. Although Sands is the main character, the film is well underway before he is introduced. The movie begins by telling the story of two other Maze prisoners, Danny Gillen (Brian Milligan) and Gerry Campbell (Liam McMahon).

The prison guards process Gillen on his first day of confinement. He declares himself a political prisoner, and refuses to wear the prison uniform, so he is led to his cell naked. A bloody gash is visible on the back of his head as he is taken away, but we do not see the beating take place. We see plenty of violence later on, but the off-screen terrors are more affecting. Imagined brutality has a more lasting effect than the real image.

I remember the killing scenes in “Slaughterhouse 5”, “Life is Beautiful” and “M” much more vividly than any of the killings in “The Godfather” or “Reservoir Dogs”, and in those first movies I mentioned, we never see the actual killing.

Gillen is placed in a cell with Campbell, a cell that would make Bernie Madoff’s white box in a lower Manhattan jail look like a suite at the Sherry Netherlands. Campbell’s walls are smeared with human waste; his left-over carrots and mashed potatoes are piled in clumps on the floor and covered with flies; and Campbell himself is unshaved and unwashed, a self-styled Count of Monte Cristo without the pedigree or a country to call home.

McQueen shows both sides of the prison struggle, a microcosm of the Irish “troubles.” Prison guard Raymond Lohan (Stuart Graham) inspects the underside of his car for explosives every morning before he goes to work. He knows that, because of his job, he is a marked man. He sports bruises that look similar to those of the prisoners. They are red and ugly, and cover the knuckles of both his hands. He must regularly soak them in a prison sink.

As with the bruise on the back of Gillen‘s head, we don’t immediately see how Lohan gets his scars, or how his shirt is constantly stained with sweat. McQueen gives us the information eventually, but by withholding a lot of it, at first, he makes its eventual impact much stronger.

Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender) first appears as a long-haired, bearded, dirty and violent prison inmate. The guards chop his hair off, throw him in a tub, and scrub him with an industrial floor brush. Riot guards beat him as he is led to and from the tub.

He kicks and spits his way through the entire ordeal. Once cleaned up, the handsome and articulate, although badly bruised, Sands has a conversation with a visiting priest, Father Moran (Liam Cunningham) who tries to talk Sands out of his planned hunger strike.

The heretofore quiet film now has quite a lot to say. The camera never moves during this long scene that has the tight focused feel of a one act play. The two men smoke one cigarette after another, and debate the morality and the practicality of selecting a cause, the role of principle in maintaining that cause, and how far a commitment to that cause can and should go.

Opinion shifts back and forth between the two men as each mounts his own high horse to joust with the other. No compromises are reached, and neither side moves to accommodate the other’s point of view. They do seem to agree, as does McQueen, that adhering to a principle can be virtuous, but that the same principle can be dangerous when it is separated from other virtues and is devoid of mercy and understanding.

Principle by itself allows us to exercise many options in the defense of that principle. A united Ireland is indeed a principle. Perhaps it’s an honorable principle. However, does that principle permit one to take a life, especially an innocent life, in order to uphold that principle?

The Maze prisoners, unfairly treated by the prison guards, would say yes. McQueen reveals the bloody handiwork that lies behind the prisoners’ principles. The prisoners pass secret messages to their girlfriends who visit them in prison, and that information results in actions that are as childishly attention seeking as they are psychopathically cruel.

The last twenty minutes or so of the film take us through Bobby Sands’ hunger strike. Step by step we watch the stages of human starvation and dehydration: the emaciating muscles, the sinking cheeks and hollowing eyes, the breaking down of skin and mucous membranes, the infection winning its battle against the body’s defenses, and the laboring of breath.

We watch a process that is painful and slow. In this movie, we see what we could not see several years ago when a Florida woman was dehydrated and starved in accordance with a court order. During that ordeal, the press wrote about music in the background and an air of peace inside that hospital room. This movie shows in visual detail the reality of what hunger and starvation actually do to a human body.

McQueen does his best to make a fair film, but his sympathies lie with the weak against the strong; in this case, with the prisoners against the prison system, and against the British government, and especially against Margaret Thatcher. The British—and the Irish—left cannot let go of Thatcher as a bete noir. At least the American left has eased up on Ronald Reagan.

American leftists have found new targets, but the fire that their British counterparts direct at the former Prime Minister is still red hot. I just got back from seeing the current Broadway version of “Billy Elliot,” which is not so much a musical as a two and a half hour anti-Thatcher polemic with a few unsavory tunes thrown in for background.

McQueen is an artist by trade—a famous one, I’m told, although I’m not familiar with his paintings—and his film looks like a painting. It may be stretching it a bit to say that the smeared prison walls look like Van Gogh’s starry night skies (okay, the color is different) or the prison scenes, especially the ones of Stuart Graham standing alone in the snow have the dreamlike feel of many of J.B. Yeats’ pictures.

In 1981, I strongly disagreed with Bobby Sands’ hunger strike. I still do. But McQueen has dramatized Sands’ story in a way that gives me a better understanding of Sands’ life and the courage that moved him to make a decision and to accept the consequences of his decision. I saw the movie about the same time that a group of University students in New York City (where I live) took over the cafeteria of the college to make a series of demands.

There was no hunger strike; in fact, Whole Foods was able to cross the protest line in order to make deliveries to the diet conscious students. The protesters’ demands were the usual ones: environmental protection, disinvestments in Israel, etc., etc. But what was the first item on their list of demands? They insisted on complete immunity from any disciplinary consequence that might result from their protest.

Bobby Sands may have been misguided, but his choice had a consequence, and he accepted that consequence. McQueen also reveals, again quietly, the strength and the compassion of the people who supported and cared for Bobby Sands. His parents and his caretakers in the prison treat a dying and decomposing man with love and respect. No matter how much Sands’ condition deteriorates, his attendant does not abandon him; on the contrary, the orderly takes extra care with Sands’ crumbling body. He treats Sands as a human being whose soul and body are worthy of love and respect no matter what condition either is in.

“Hunger” has many violent scenes and frequent male nudity. There is a scene in which Bobby Sands rolls his cigarettes with pages from a Bible. The film nonetheless addresses relevant moral, ethical and political issues. Twenty eight years after the Sands hunger strike the politics have changed—how those winds blow this way, then that way!—but morals and ethics that underlay the case, especially the morality of how we look at and how we treat human life, have not.

- Violence: Heavy

- Profanity/Vulgarity: Heavy

- Sex/Nudity: Extreme

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.