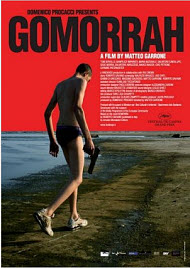

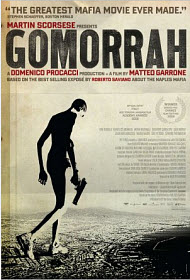

Gomorrah

Canada: 14A and 13+

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Very Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Crime Drama |

| Length: | 2 hr. 17 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2008 |

| USA Release: |

October 3, 2008 (New York Film Festival) November 2, 2008 (AFI Los Angeles International Film Festival) December 19, 2008 (Los Angeles, California) February 13, 2009 (limited) DVD: November 24, 2009 |

Murder in the Bible

What are the consequences of racial prejudice and false beliefs about the origin of races? Answer

NUDITY—Why are humans supposed to wear clothes? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

| Salvatore Abruzzese, Simone Sacchettino, Salvatore Ruocco, Vincenzo Fabricino, Vincenzo Altamura, Italo Renda, Gianfelice Imparato, Maria Nazionale, Salvatore Striano, Carlo Del Sorbo, Vincenzo Bombolo, Toni Servillo, Carmine Paternoster, Alfonso Santagata, Massimo Emilio Gobbi, Salvatore Caruso, Italo Celoro, Salvatore Cantalupo, Gigio Morra, Ronghua Zhang, Manuela Lo Sicco, Marco Macor, Ciro Petrone, Giovanni Venosa, Vittorio Russo, Bernardino Terracciano |

| Director |

|

Matteo Garrone |

| Producer |

| Fandango, Rai Cinema, Sky, Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali, Laura Paolucci, Domenico Procacci |

| Distributor |

| IFC Films |

The Italian film, “Gomorrah”, takes its name from the second of the doomed twin cities of the Old Testament. Impending destruction lurks in the movie’s modern day counterpart, the Camorra crime world of Naples, Italy—the title is also a play on words—a regime so steeped in evil that only a cataclysm can rescue it. The new Gomorrah sees its Biblical counterpart, and raises it. The new city’s sins go deeper than the earth; they dig, burrow, and settle into the civilization’s very foundation.

“Gomorrah” was directed by Matteo Garrone and is based on the book by Roberto Saviano. The Camorra have a bounty on Saviano’s head, so the author now lives under police protection.

Most of the action in “Gomorrah” takes place in a dilapidated apartment building in a Naples slum. Dirt, dust and grime are everywhere. The Camorra’s daily routine consists of testing, prepping, and dealing drugs; packaging, running and firing guns; and collecting, counting and doling out collection money. In between these activities, they kill for revenge, advancement, and amusement. Some strive for something more by moving into the garment business or into waste management, but even those enterprises turn corrupt and deadly.

The underworld that Garrone depicts is a far cry from the Hollywood vision of organized crime. “The Godfather” movies, “Goodfellas”, and even the ironic “Prizzi’s Honor” mute the evil of La Cosa Nostra by giving equal or a good deal more time to the sheer allure of crime. Henry Hill’s nightclub entrance in the extended opening scene of “Goodfellas” has enough temptations to produce a high that can override the examination of conscience that would make us run from Hill instead of identifying with him.

I always thought “The Godfather” movies were more soap opera than art. “Gomorrah” comes closer to an artistic achievement. It does so without the kind of artifice that weighed down all of Copolla’s films and sank “The Godfather Part III”. “Gomorrah” has no lavish baptisms, no favors granted with a kiss, no cats on the lap, and no cannolis to sweeten the death scenes.

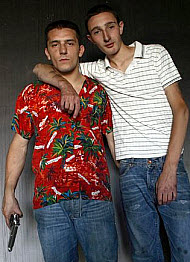

The film opens in a tanning salon. I thought that the bronzed and beefy wise guys lounging under the blue lamps would soon be sunning themselves on deck chairs on a yacht in the Mediterranean. That is not what happens. Outside the salon, there is no “Under the Tuscan Sun” shimmering sea. We get glimpses of the coastline, but it is no oasis. It is littered with the same debris that pollutes the Naples slum. Two of the young characters use the beach for AK-47 target practice. Unleashing their destructive capacities causes them to leap with glee. They turn abandoned fishing boats into fireballs, and howl when those remnants of a bygone civilization go up in flames.

Garrone tells many stories simultaneously. Pre-teen boys train for careers in the Camorra by taking gunshots to their bullet-proof vest covered chests, running drugs, and setting up neighbors for mob hits. Teenage boys brag about their ranks on the syndicate chain depending on who is pulling that chain at any given time: “I’ll live for thirty years if he’s the boss here,” proclaims one youth with much bombast but with no irony. A money distributor who has been struggling for a long time in a business in which men tend not to last a long time is treated as a lackey and a stooge by both the lenders and the borrowers. A dressmaker puts his heart into his creations, haute-coutre designs that are worn by the rich and famous (he sees actress Scarlett Johannsen wearing one of his gowns on television), but bring him no recognition or financial reward. His Camorra patrons guide him and nurture him, but only so they can take everything from him.

The most disturbing story is about a man who makes his living in toxic waste elimination. His trucks are filled with drums of contaminated refuse. He gets young boys to drive the trucks into deep quarries outside of town where the waste will be dumped and buried. The drums of refuse percolate beneath the corruption that brews on the surface.

Some critics have said that “Gomorrah” represents a resurgence of Italian Neo-Realism which became a strong cinematic force after World War II. I don’t see the similarity between the two filmmaking styles. The realism of the earlier period was immediate, and often fierce and gritty, but it had some heart as well. The children in “Gomorrah” couldn’t be more different from little Bruno in “The Bicycle Thief” or the two lost boys in “Shoeshine”. Even in the desperate ruins of post-Fascist Rome in Rossellini’s “Open City” there is some hope. There is no hope in “Gomorrah”, but it gives us an unfiltered look at what crooks do and who they are. They are not smart, and they are not glamorous. These are the real-life Mafia losers we see on the pages of the New York Post whose wasted and flabby frames can barely fit through the doors of a paddy wagon. They live like pack animals on the run: youngsters trying to outdo other youngsters so as not to be marked as prey; aging men trying to stay a little bit ahead of the young to spare themselves from being the next sacrifice; no one far enough ahead of the wolf to ever feel safe.

Gomorrah, and its sister city, Sodom, shows us what happens to a civilization built upon the will of man and the promises of false gods. The film, “Gomorrah”, shows us a modern day society built on those same tenets, and enslaved by sin. Only one character has the insight, and the grace, that allows him to turn away from the burning city and to seek salvation. His epiphany occurs on a road which leads away from one of those toxic quarries. That road is long and lonely; the road to salvation always is.

“Gomorrah” is in Italian with English subtitles. There is frequent use of foul language, constant violence, and one scene of female nudity in a strip bar. The movie strives for a realistic tone and effect. It is successful in that goal, but it is harsh and offers no solutions to the evils it portrays.

Violence: Heavy / Profanity: Heavy / Sex/Nudity: Heavy

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.