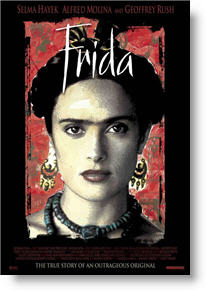

Frida

for nudity, sexuality, and language.

for nudity, sexuality, and language.

Reviewed by: Dr. Kenneth R. Morefield

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Very Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Romance Drama |

| Length: | 2 hr. 3 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2002 |

| USA Release: |

| Featuring |

|---|

| Salma Hayek, Alfred Molina, Antonio Banderas, Ashley Judd, Geoffrey Rush |

| Director |

|

Julie Taymor |

| Producer |

| Lizz Speed, Roberto Sneider, Jay Polstein, Nancy Hardin, Liz Speed, Lindsay Flickinger, Salma Hayek, Sarah Green |

| Distributor |

Salma Hayek plays the Mexican artist who strove to overcome a near-fatal accident as a child and a stormy marriage to fellow painter Diego Rivera (Alfred Molina). **Warning: Some Plot Spoilers in this Review**

Oddly enough, the film “Frida” most reminds me of is “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets”. Despite the films numerous differences—one a major studio release, the other an art-house film; one a children’s/family film, the other a biography by and for adults—both suffer from the same major flaw: a devotion to its source material that makes it strain to fit everything in but never allows it to reflect on its meaning. Not that this flaw is incomprehensible. Kahlo lived a fascinating life. Her ability to succeed as an artist in a time and place where being a woman was handicap enough lends a triumphal air to story which has helped catapult her reputation beyond regional artist to that of cultural icon. Still the fullness of her life tends to give the film a sort of “and then this happened, and then this happened, and then this happened” quality.

Although “Frida” is not a very reflexive film, it does try to erect a central theme around Kahlo’s marriage to Rivera. Rivera, a serial adulterer, claims he is not capable of “fidelity.” Kahlo responds that this is okay as long as he shows “loyalty.” What exactly this distinction means was lost on me, though the film seemed to think it important. (It apparently has something to do with it being okay for Rivera to sleep with other women as long as they are not Kahlo’s sister, although even here she eventually takes the blame for his actions by saying, “I never should have put them in the same room together.”) Isn’t fidelity substantially loyalty in the sexual realm? Putting aside the old rube that if he cheats with you he will cheat on you (a young Frida breaks into a studio where Diego is having sex with a model and is caught by his then wife), the film gives no real explanation as to why Kahlo expected Rivera would treat her any differently (because she was an artist? because she shared his socialist ideals?) or whether, in fact, she really did. The most logical explanation of her attitude towards his adultery is that it is similar to Carmella Soprano’s on the HBO television series: she lives in a culture where she can’t really have much of a life outside of marriage and which accepts male adultery without comment.

One of the most heartbreaking elements of Kahlo’s life is that she lived in near-constant pain as a result of a childhood accident. The film has a problem in how to convey long periods of hospitalization at regular intervals—the elements of her life that were the most cinematic were the ones that happened in the spaces around the constrictions life placed on her. And yet by jumping from episode to episode, the film undercuts the depths of those (physical and cultural) restraints. Yes, she is constantly saying she is in physical pain (as she is dancing a tango or climbing a pyramid) but we see little of the cost that the constant drain of energy exacts on one’s soul. Kahlo, in real life, did accomplish a lot physically. She apparently had a near-manic power to push her body as a way of attacking her pain. So it is not as though the things the movie shows her doing are inaccurate. But in the physical realm, as in the relational one, we have a lot of focus on what she did to the exclusion on what why she did it or what it signifies.

The best moments in “Frida” were the ones when the woman, like her paintings, didn’t speak, but we saw (or thought we did) the explanation(s) in her jaw, her brow, and above all her deeply penetrating eyes. These moments lasted a second and then the camera cut away from her face in a rush to tell me what happened next.

“Frida” knows a lot about Frida (and is anxious to tell us), but I think five minutes of real reflective space would have better served its subject matter than an hour of plot detail. My Grade: B-

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5